“Unlike the Loch Ness monster, the Wolverhampton beast was far from timid…”

Today’s story is a Halloween-themed tale of confusion, “monsters” and children playing. Yet rather than occurring in October, this story dates to January of 1934. At the time, few thought much of a young boy’s account of a “monster” which attacked and bit him, dismissing it as nothing more than the work of a stray dog. But just a few days later, the beast would be discovered.

A Place Called Brickkiln

Brickkiln Croft is a place which no longer survives in modern Wolverhampton, but would have been roughly where the proposed Westside development is set to be built. This small street would have been a slum area, made up of back-to-back housing comprising of a series of small courts. By 1934 the area had largely been cleared and lay as waste ground, and an area in which children could not resist the urge to play.

On 16 January, 1934, local children were playing in the area, when a rodent-like creature appeared and was said to have ‘attacked two boys’. George Goodhead, 17, retaliated against the unknown assailant, and he and the other children stoned the creature to death. Upon gazing down, they described the following:

A head like a small boar; a snout and protruding teeth; front legs like those of a large rat, a rat-like tail about 16 inches long. The beast is shaggy-coated and measures 38 inches from its snout to the tip of its tail.

The Birmingham Gazette, 17 January 1934

‘I Have Never Seen Anything Like It’

Upon the story breaking, the press contained much speculation as to the creature’s identity, with some believing it to be ‘a cross between a mongoose and a rat’. A veterinary surgeon who had seen the carcass declared, ‘I have no idea what it is. I have never seen anything like it before, but it looks like a rat.‘ The surgeon further posited that a taxidermist might be best placed to determine its identity.

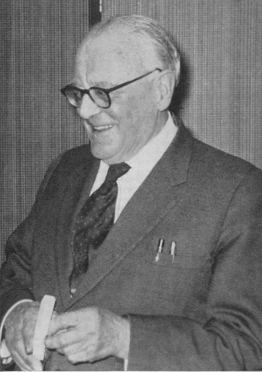

The creature was taken away to council premises on School Street, and far from being taken to a taxidermist, was taken to a medical man of significantly greater seniority. The man given the task of identifying the creature was none other than the Director of Pathology at the Royal Hospital, Dr Sidney Campbell Dyke.

The Doctor’s Diagnosis

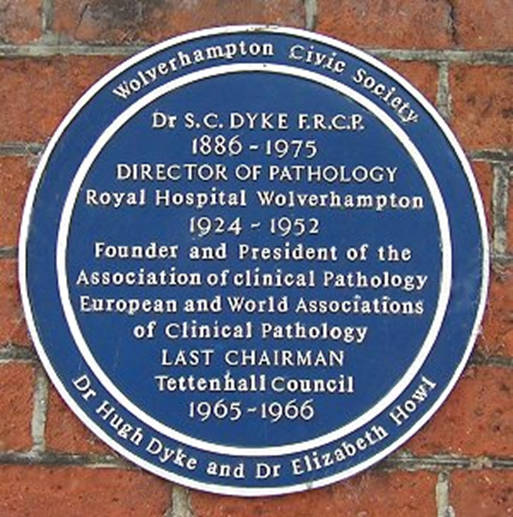

Dr Dyke is commemorated via a blue plaque in Limes Road, Tettenhall and was a hugely regarded figure in both the medical world and the local community. Originally born in Surrey in 1886, he emigrated to Canada, where he earned a first-class honours degree in art in 1909. He returned to England and completed another degree in the natural sciences at Oxford, before joining King Edward’s Horse (The King’s Overseas Dominions Regiment) during WW1. He would eventually complete his studies and joined the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). He would move to the Royal Hospital, Wolverhampton in 1924 and remained there until his retirement. Amongst Dr Dyke’s many achievements he is particularly noted for setting up the Association of Clinical Pathologists, an organisation which still exists today.

An individual of such calibre was required to determine the identity of the mysterious “monster”. It is difficult to think of this now, where we live in a world where one can Google anything they so desire, but the origin of the creature was such that few would have had an accurate idea of what it was. In any case, the learned Dr Dyke delivered his verdict; the animal was in fact a coatimundi.

Lost In a Strange Land

The coatimundi is not commonly associated with the British Isles, and is instead native to South America, Central America, Mexico, and the southwestern United States. Coatis are not big enough to pose a serious threat to human beings, but they do eat a variety of other creatures, such as lizards, rodents and small birds. They are known to be fierce fighters when provoked, and have sharp claws and teeth and strong jaws. It is no wonder that a lost, frightened animal would be extremely defensive, and indeed, it is no surprise either that the children reacted in a similar manner. With the poor beast dead, the question ultimately became how did it arrive in Wolverhampton?

Just Passing Through

Despite Dr Dyke’s assertion that coatis were ‘harmless’ and made ‘good pets’, it was highly unlikely that anyone in the town would have taken such an exotic creature as a pet. It was even more unlikely that said pet would have escaped and made it all the way into the centre of the town.

Eventually, it was noted that a travelling zoo had passed through Wolverhampton on 15 Monday, 1934, and this was identified as the likely origin of the South American visitor. In addition, on the day of its identification, a second (female) coatimundi was found dead in a brick kiln in the area. The vicinity was checked for further “monsters” and none were found.

And thus, the mystery of the “Wolverhampton Monster” was solved.

Further Reading

The story of Wolverhampton’s forgotten boxing champion…

The tales typewriters can tell…

Sources Used

The Birmingham Gazette, 17 January 1934

The British Medical Journal, 22 March 1975

Edinburgh Evening News, 19 January, 1934

Nottingham Evening Post, 19 January 1934

The Scotsman, 22 January, 1934

Leave a Reply