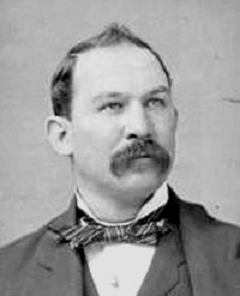

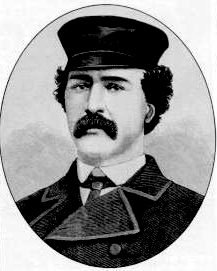

Throughout part of his career as a pugilist, Joe Goss was referred to as “The Unknown”. It is a nickname that now, nearly a century and a half after his passing, seems more apt than ever. Once famed throughout England, Goss would later move to America and become the figurative “Heavyweight Champion of the World”. At the time, in 1885, his funeral in Boston, MA, was said to be the largest the city had ever seen for a sportsperson. But just who was “The Unknown”?

The Son of a Shoemaker

Joseph Goss was born in Northampton on 6 November 1837 to Joseph Goss, a shoemaker, and Elizabeth (nee Spencer). He was the fifth son of a family of 8 boys and 8 girls. Goss grew up in the family business and trained as a shoemaker. It was not until Goss’ later teenage years his interest in the sport of boxing began to pique. Every year, a great Whitsuntide Fair was held in Wolverhampton, and Goss visited this event in 1858. He is said to have “entered a sparring booth” and was clearly enamoured with the sport. He would go on to have two fights which were not contested under rules of the Prize Ring.

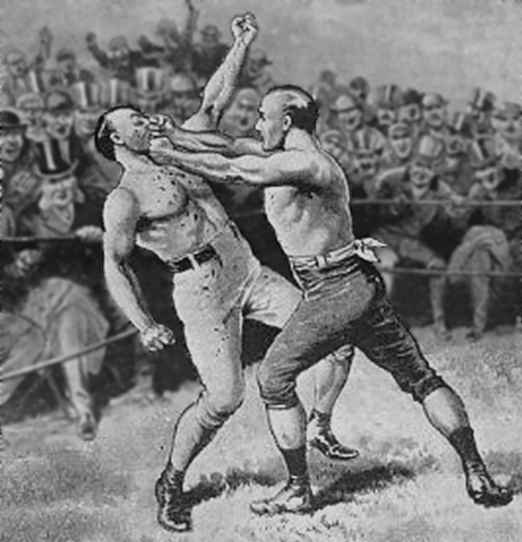

For most of Goss’ career, he fought under the London Prize Ring Rules, the forerunner to the Marquess of Queensberry Rules which largely still govern boxing to this day. These rules were considerably more brutal, with fights being bare knuckle affairs which would essentially run until a man could fight no more. Whilst there were rounds, these only ended when a man was downed by either a throw or a punch. At the end of rounds, men were given 30 seconds to rest, followed by an additional 8 seconds to “come to scratch” – scratch being a line scratched into the ground in the rough centre of the ring. Fights were won either via traditional knockout, or by one fighter failing to come to scratch.

Side note – if you were wondering, yes, this is where the phrase “up to scratch” is from.

Joe Goss Goes Undefeated

Joe Goss had a meteoric rise in the ring and remained undefeated for some time. Despite later fighting for the “Heavyweight” title, he would usually weigh in between 145-160 lbs. The modern equivalent is somewhere between Welterweight (Floyd, Manny, Khan, etc) and Middleweight (Canelo, GGG, etc). Throughout 1859-60, he defeated Jack Rooke, a Birmingham-based Irishman; Tom Price, a pugilist from Bilston, and Henry “Bodger” Crutchley, a brother in-law of famed Birmingham fighter, Bob Brettel. It is important to note that the men of this period should not be considered “enemies”; they were simply a fraternity willing to fight each other for money. Fighters often seconded others to the ring, and Goss’ opponent of 1859, Jack Rooke, would be a witness to his marriage 4 years later.

Goss would continue fighting throughout 1861, taking on another protégé of Bob “The Birmingham Pet” Brettle. Bill Ryall was a large man, standing around 5’11” tall, and carried over a stone weight advantage on Goss. His physical traits earned him the nickname, “Bob Brettle’s Big ‘Un”. The fight would be Ryall’s debut and he gave an excellent account of himself, overwhelming the durable Goss for much of the fight. A change was noticed at the end of the 24th round; Ryall had thrown Goss, but had inadvertently landed on his own head. Goss proceeded to largely beat Ryall up for another 13 rounds, before the towel was finally thrown in.

More Wolverhampton Connections

Around this time, Goss started to train out of a pub on Great Brickkiln Street called the Old Boat Inn. It’s unclear why such a land-locked pub would have such a name, but in any case, it ceased to exist around the turn of the 20th Century. The then-proprietor, Thomas Savage, would also be involved in the fighting trade to some degree, as a backer. Goss’ own father strongly disapproved of his son’s decision to box, and Savage would have a paternalistic relationship with Goss Jr. Initially this was purely from a training perspective, but would later become one of law, with Joe marrying his daughter, Eliza, in 1863. The relationship between the two families would be further cemented in 1870, when Thomas’ son, William, married Goss’ sister, Charlotte.

Back in the boxing world, calls for a rematch with “Brettle’s Big ‘Un” had intensified and the match would duly take place on 11 February, 1862. Thanks to unscheduled interruptions by the law, the match would transpire across three separate rings. Goss was badly injured in the third round, breaking a bone in his shoulder, but both men would continue on for 34 rounds, until the match was declared a draw. Much of Ryall’s sluggish performance was attributed to him taking charge of the Broad Street Tavern in central Birmingham. He allegedly weighed 14 stone at the beginning of his training camp – perhaps Ryall was the Victorian-era equivalent of Ricky Hatton.

The Best and Worst of Times

Goss’ next fight would be against a veteran of the Midlands boxing scene, Edward “Posh” Price, of Birmingham. Posh had taken part in around a dozen (or more) fights, with only a loss (to Jem Mace) and a draw (to Bodger Crutchley) staining an otherwise perfect record. On 25 November, 1862, Goss emerged victorious after 66 gruelling rounds, passing what was his toughest test yet. With Posh Price’s only defeats coming to Jem Mace and Joe Goss, the stage was set for the two to collide.

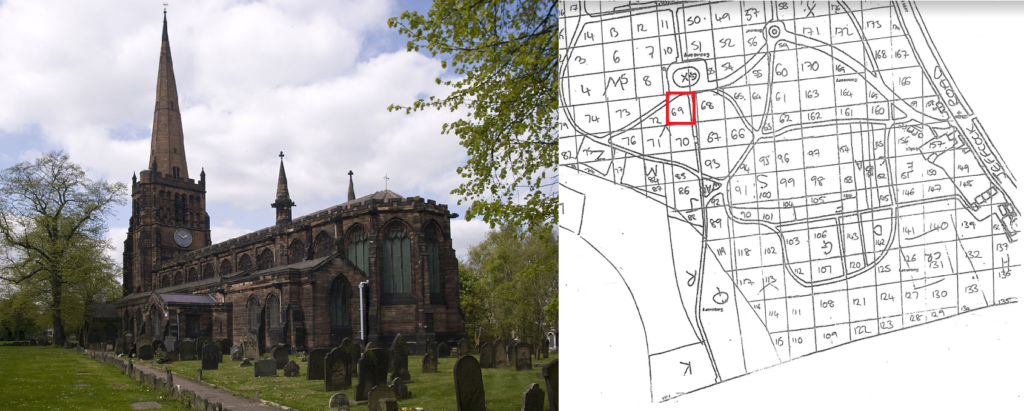

On 21 February, 1863, Joe Goss married Eliza, the daughter of Thomas Savage, at St Peter and St Paul Church, Aston. Jack Rooke and his wife, Caroline, were witnesses to the marriage. Joe lists his place of residence at the time as Duddeston (in Birmingham), which is unsurprising, given the number of other fighters who lived in the area at the time. His trade is still listed as ‘shoemaker’ at this point. Whatever plans Joe and Eliza had at this point, they would be cruelly cut short, when, on 6 May, Eliza passed away from peritonitis. Joe’s first marriage would not even last 75 days.

Whether the tragic events of spring 1863 had any significant impact on Joe, we are unlikely to ever know, but regardless, the drums for the fight with Mace banged louder than ever.

Joe Goss v Jem Mace

Now almost forgotten, the Jem Mace v Joe Goss fight for the Middleweight Championship of England was a huge event at the time. The fight was so big that on 29 August, 1863, Sporting Life stated it would print 250,000 copies of its report of the fight in time for the morning after it. Bear in mind that the UK population at the time would have only been c. 18 million, and many of these were illiterate. With America in the middle of a Civil War, the English titles were the pre-eminent ones of their day.

The contest itself ended after 19 rounds with victory for Jem Mace. Goss would ultimately never better Mace, suffering a defeat in 1866 for the Heavyweight Championship of England, and a draw in a rematch three months later. Despite their rivalry, Goss and Mace became good friends, working together, and sparring exhibitions with each other regularly.

Just three months after the first Mace fight, Joe would be back in action, defeating Ike Baker, of West Bromwich, in 27 rounds on 16 December, 1863.

The One That Got Away

Goss would challenge for the Middleweight Championship again, this time against Tom Allen, of Birmingham. The fight took place on March 5, 1867, and would end in a stalemate after 34 rounds had been completed, and following another police interruption. Goss would have to wait to meet Allen for a serious crack at a belt again, some 9 years later.

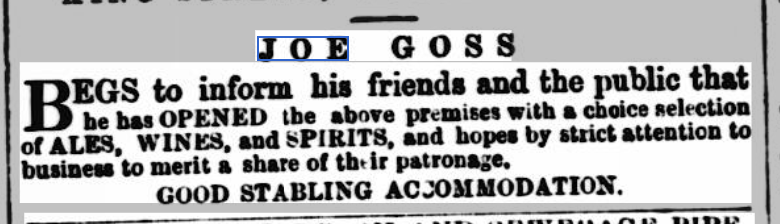

Another attempt would be made for the Championship with Harry Allen on 1 September 1868, but the police again saw to this being interrupted and recorded as a draw. In December 1868, like so many of his fighting brethren, Joe took on the running of a pub, becoming the licensed victualler at the Saracen’s Head on King Street, Wolverhampton. The site is still a pub to this day, but was altered substantially at some point in the late 19th Century, and now lives on as the Old Still Inn.

In 1871, we find Joe resident on the day of the census, alongside a wife, Ann E. Goss. As yet, I have been able to find out very little about this second relationship.

Joe takes a break from fighting at this point, and is aged 34. By now, Joe had seen numerous run-ins with the law, both in terms of prize fighting, and other assaults. In addition, a number of his former friends and foes had passed on. The London Prize Ring rules were brutal, and Posh Price, Brettel’s Big Un’, Bodger Crutchley and Bob Brettel himself would all be dead before Goss would leave for America. Seemingly showing a desire to settle down, Goss would run his pub in Wolverhampton for six years, and his fighting days – both in and out of the ring – seem to be behind him.

Despite the term ‘prizefighting’, boxers earned very little money, even if relatively successful, like Goss had been. In May 1873, Goss owed money to creditors and his estate was liquidated. He would, however, continue to run the Saracen’s Head until December 1875, when the license was transferred to Joseph Gibbons. On April 15, 1876, Goss would arrive in Boston, America, with his good friend and rival, Jem Mace.

Shipping Up to Boston

Joe Goss’ career in America, though relatively brief, would merit an article of its own. Much of his time would be spent fighting exhibitions, but on September 7, 1876, Goss would face Tom Allen again, this time for the Heavyweight Championship of America. The match would end in victory, as Allen was disqualified for striking Goss while he was down. Joe had become the Heavyweight Champion of America, the proto-World Champion, at the age of 38.

Goss kept the belt until 1880, when he was defeated by Paddy Ryan on 30 May, 1880 in New York. Joe would take up residence in Boston, MA, opening another bar called the Saracen’s Head Inn, at 22 Lagrange Street. He would fight a few exhibition bouts with future Heavyweight Champion, John L. Sullivan, and become friendly with him. Joe’s last bout was with Sullivan, and took place on December 14, 1882, when Joe was 45.

The Final Bell

Joseph Goss passed away on 24 March, 1885, at his pub, The Saracen’s Head, in Boston, MA. The cause of death was attributed to Bright’s Disease, which in modern terms would be known as Nephritis, or a severe kidney infection. Goss was not alone in succumbing to this; both great engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and baseball legend, Ty Cobb, suffered from the same debilitating affliction.

Goss’ funeral was a sombre, yet impressive affair. It was noted that to enter the room was “like entering a conservatory, so powerful was the perfume of the abundant floral tributes.” The casket carried a silver plate which read, “JOE GOSS. DIED MARCH 24, 1885. AGED 49.” Perhaps it was the travel, or working in a field which involved repeated blows to the head, but Joe was in fact only 47 in the year of his passing.

On top of the casket was a floral pillow, marked simply, “My Husband”, alongside dried wheat spelling out, “Rest.” One half of the room was occupied with floral tributes from friends, with John L Sullivan sending two exquisite pieces, representing “the gates ajar”. Goss had lived long enough to second Sullivan to the ring for a fight with his conqueror, Paddy Ryan in 1882. Sullivan would prove victorious, and just 5 months after Joe’s passing, he would go on to win the inaugural Heavyweight Championship of the World.

As the pallbearers transported Joe’s coffin to the hearse, it was said that the number of mourners was “thousands standing in solid rows, extending from Tremont to Washington Street, and completely filling every available space.” Furthermore, “The windows of the houses on both sides were filled with men and women and children to their utmost capacity. It was the largest funeral ever recorded to a sporting man in Boston.“

Joe is buried at Forest Hills Cemetery, Boston.

So Who Was Joe Goss, “the Unknown”?

Goss was quick, crafty, and durable; He was a skillful pugilist under [the] London Prize Ring Rules and knew all the tricks.

http://www.cyberboxingzone.com/boxing/goss-j.htm

It is probably fair comment to say that Joe Goss was an excellent boxer, but not a truly elite one. He never bested the man in his era, Jem Mace, despite three attempts at this. Whilst he never beat Mace, during his prime (pre. 1876), no one other than Mace defeated him. Whilst Goss won the belt via disqualification, he was Heavyweight Champion of America between 1876-1880. It is perhaps unfortunate that Joe was not born around 5-10 years later, when rule changes led to Heavyweight Champions became officially recognised.

If one was to try and give a modern day comparison, Mace would be the Victorian era equivalent of Floyd Mayweather, and Goss more of a Miguel Cotto; a tough, skilled boxer, who would lose to a handful of elite fighters, but still be able to win titles.

Joe Goss is recognised by the International Boxing Hall of Fame, having been inducted into the Pioneer class in 2003. Regrettably, his achievements are not noted in the UK city which he made his home. Goss spent the best part of 20 years in Wolverhampton, marrying a local and running a pub in the city centre, yet he is not remembered in the present day. There is considerably more to his story than it was possible to detail here and I am happy to offer talks on his life and that of fellow local fighters. I’m also currently researching a book on the topic, set to be titled, ‘Barely Legal: Boxing’s 19th Century Struggle to Become a Sport‘.

Joe Goss deserves to be remembered in some way by the city of Wolverhampton. Whether it be in the form of a plaque, a boxing trophy, or something similar, his achievements should be noted. It’s time to let the unknown be known once more.

If you have any information about Joe Goss, or any other Midlands bareknuckle boxers, please get in touch via the form below, or leave a comment. Thank you.

Leave a Reply